“Just get out of the way”

Last October, the East Troublesome megafire became the second-largest Colorado wildfire in recorded history. What happens now?

By Katchene Kone, Anna Haynes and Harrison Daley

At around 8 p.m. on Oct. 21, Jodie Kern, a 911 dispatcher for Grand County, Colo., and her husband, Donnie Kern, were having dinner at their house. Their home in Columbine Lake, which is about one mile northwest of Grand Lake, wasn’t even in the pre-evacuation stage. They weren’t worried about the East Troublesome Fire reaching their home.

But then it got dark.

“It was too early in the night for it to be that dark,” Jodie said. “(We) went outside on our back deck, and could just see... ash on everything. And the wind started to howl. And we could hear the fire from outside. It was just super black. (You) couldn't see anything, but you could just hear this growl of the fire. It was the craziest sound I've ever heard.”

The appropriately-named East Troublesome Fire was first reported on Oct. 14, as a small fire near Hot Sulphur Springs. Within one week, it became uncontrollable.

Winds, at times exceeding 100 miles per hour, kicked up and the fire flared to unimaginable life. In three days, the fire grew more than tenfold. Seasoned firefighters described it as incredibly huge, unlike anything they had seen before.

Prior to 2020, the largest fire in Colorado had been the 2002 Hayman Fire, which incinerated nearly 140,000 acres. But conditions in 2020 fanned East Troublesome to more than 192,000 acres.

The East Troublesome Fire is classified as a megafire, which the U.S. Interagency Fire Center defines as a fire that burns more than 100,000 acres. Interviews with survivors who fled the fire, the fire officials who eventually suppressed the fire and the experts who are now assessing and mitigating the damage make it all too clear: a fire as unprecedented as East Troublesome requires an unprecedented response.

A screenshot captured by a security camera from a house on Jodie and Donnie Kern's block that burned on Oct. 21. The car behind the trees is Jodie's car as she evacuated the area. Courtesy of Jodie Kern.

Jodie and Donnie Kern's home before it was destroyed in the East Troublesome Fire Oct. 21. Courtesy of Jodie Kern.

The remains of Jodie and Donnie Kern's house following the East Troublesome fire. Courtesy of Jodie Kern.

Jodie and Donnie Kern, to their surprise, were ordered to evacuate. They began loading their belongings, like photo albums and guns from Donnie’s father, into their car.

“I went out to put some things in the car and there was this crazy big red glow off to the west from us. And everything else was just dark,” Jodie said. “Super, super dark.”

“I hollered into the house for (Donnie) to come and look, like, ‘You have to come see this red glow, it’s super crazy,’” she said. “Not even thinking, like, ‘That's the fire right there.’”

“We walked out from under our garage to the end of our driveway, which was probably about 200 feet or so,” Jodie continued. “And by the time we got to the end of our driveway, our neighbor's property was on fire.”

Several trucks sit side by side on a dirt road, their headlights creating beams in smoke, as the blood orange sky glows overhead. Photo taken on October 21, near Highway 125 in Grand County. Courtesy of Ben Freeman.

Meanwhile, major fires burned elsewhere in the state. The Pine Gulch Fire went on to top the Hayman in acres burned. Before the season was out, fire experts like Olson worried East Troublesome might join what became the state’s all-time largest – the Cameron Peak Fire, at nearly 209,000 acres.

Thousands of acres of beetle-killed trees, forces of climate change and a lack of thorough forest trimming combined with the massive winds to create a firestorm that leapt across the Continental Divide, sending the danger roaring to the Estes Park valley and the thousands who lived there.

Twenty-eight homes in Jodie and Donnie’s subdivision ended up being destroyed by the fire.

Schelly Olson, assistant fire chief at Grand Fire Protection in Granby, Colo. who lived half a city block away from Jodie and Donnie Kern, was out of town when the East Troublesome Fire burned her house down.

“I had worked on the Williams Fork Fire for about 50 days and was taking some R&R with a friend,” Olson said. The Williams Fork Fire, first reported on Aug. 14 in the Arapaho National Forest, spread to almost 15,000 acres.

“We just went to the beach for a couple of days,” Olson said. “And that's when it blew up.”

Nine Grand County first responders ended up losing their homes in the East Troublesome Fire. Olson was the only one from her division.

Olson has spent the last 10 years at the fire department. By founding the nonprofit Grand County Wildfire Council, she made it her mission to help the community prepare, prevent, mitigate and survive wildfire. Yet there she was, staring at the ruin that once was the house she’d worked so hard to protect, considering the irony.

“In those cases where you have such extreme fire behavior, (there) may not be anything that one can do but just get out of the way,” she said.

Schelly Olson's home before it was destroyed in the East Troublesome fire. Courtesy of Schelly Olson.

Schelly Olson standing in front of the remains of her house, which was burned down by the East Troublesome fire. Courtesy of Schelly Olson.

Though 2020 certainly counts as an aberration, a fluke of a season unlike any that came before, a daunting series of conditions suggest it won’t be the last. Fires like East Troublesome will likely become more common.

And so, Coloradans are left with the question: where do we go from here?

Thanks to fire mitigation efforts spanning over the past 20 years, the East Troublesome Fire, much of Rocky Mountain National Park remains unaffected. Photo taken April 3, 2021 by Anna Haynes.

By Dec. 1, East Troublesome had been 100% contained — but not without massive destruction. In addition to the damage done to the soil of the acres burned, officials estimate that the fire destroyed or damaged 366 homes and 214 secondary buildings, and killed two.

A combination of efforts, such as the earlier reduction of tree density, helped to slow the fire. But these wildfire prevention efforts didn’t happen overnight.

“We've been fighting this fire for 20 years,” Mike Lewelling, fire management officer for Rocky Mountain National Park, said. “Over the past 10 years, we've spent over $6 million doing these kinds of treatments on our park boundary.”

Experts have raised concerns about whether past fire mitigation efforts in Colorado have been enough. Mike Lester, director of the Colorado State Forest Service, told 9News that suppressing smaller fires and lacking forest management has led to too much fuel for fires like East Troublesome to burn through.

But after a week with no signs of the fire slowing, the accumulation of over two decades of preventative work, paired with wetter and colder weather conditions, finally did take hold.

Rocky Mountain National Park was protected from the fire by a combination of fuel treatments and a fog bank that slowed the fire on Oct. 22.

Lewelling added that if the fire kept its intensity from the day before, there would be "probably no fuel treatment in the world that would have stopped it.

"Who knows where it would have been?”

A truck parked next to Highway 125, backed by thick plumes of smoke. Photo taken on October 21, next to Highway 125 in Grand County. Courtesy of Ben Freeman.

As the fire neared Kremmling in Grand County, Ben Freeman, a firefighter from the Gunnison Fire Department, took part in protecting structures near Colorado Highway 125. At the time, the fire was still quite small, and had only burned around 20,000 acres of land.

Freeman and his crew prepped structures for the rapidly growing fire, on the east and west sides of Highway 125. They acted quickly, taking specific steps to protect homes from the incoming fire. The firefighters went from structure to structure, moving ignition sources away from them, turning off propane tanks and shutting windows. They soaked lawns with sprinkler systems, and manually sprayed trees closest to each home.

On his third day protecting structures, the fire blew up in size and crossed the highway. For Freeman and many other firefighters, the behavior of the East Troublesome Fire was unexpected.

“Really for the safety of ourselves and the people that were there, we were like, ‘Get out,’ because there was no way anything was going to stop this fire, with the winds that were going on and with the fuel moistures,” Freeman said.

Freeman and his crew momentarily pulled out of the fire. After about an hour, they returned, to continue protecting structures. They initially protected roughly 30 structures near the highway as the fire grew in size. Many engines were assigned to this area, with three to four crew members in each engine.

After the East Troublesome Fire crossed Highway 125, the firefighters immediately began calling in more resources, as well as aiding in evacuations. Thousands of people were evacuated from their homes.

“After it made its initial push, hopefully, the goal was to go in and catch the structures that weren’t already burned, or were in the process of burning, and catch them soon after,” Freeman said.

At this point, the fire significantly swelled in size, and had already reached Lake Granby. The East Troublesome Fire had traveled 20 miles from its origin. Freeman and his fellow firefighters headed up to the lake, to continue fighting the rapidly growing fire.

“Once it blew up, we were focused on other peoples’ lives at that point. The fire behavior itself was just absolutely insane. We were basically having area ignition, which means the fire and the surrounding area is getting hot enough for things to spontaneously combust,” Freeman said.

Area ignition occurs when a forest fire becomes extremely hot. The heat is so intense that smaller fires catch on in the surrounding area. These smaller fires branch off of the main fire, combusting simultaneously or in rapid succession.

Area ignition impacts the overall behavior of a forest fire. It creates conditions where the fire spreads much more rapidly. In the case of the East Troublesome Fire, this led to spontaneous combustion, which was what Freeman observed while protecting structures.

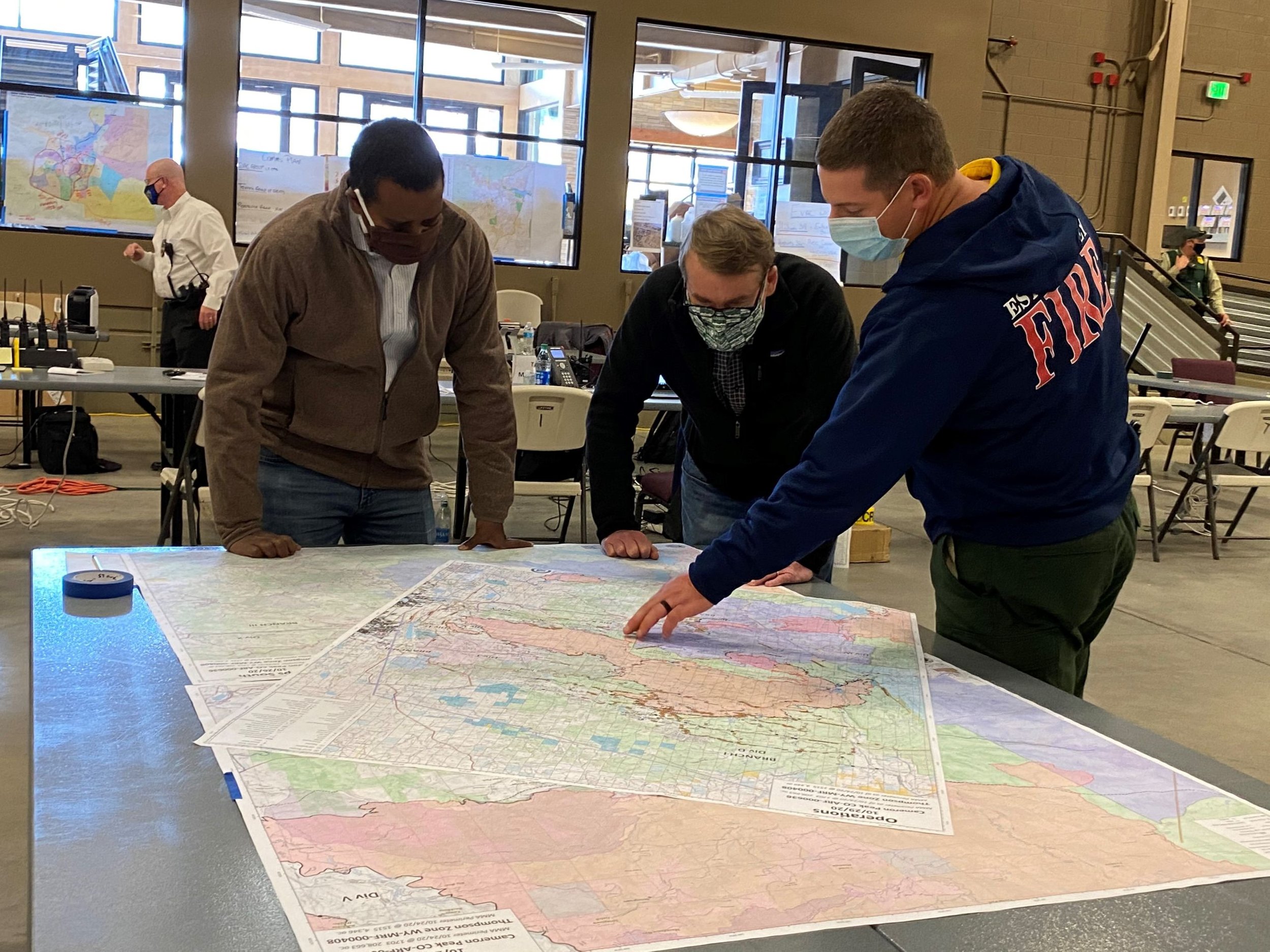

David Wolf, the Fire Chief for the Estes Valley Fire Protection District, briefs Congressman Neguse and Senator Bennet at the Estes Park Emergency Operations Center after the Estes Valley evacuations. Courtesy of David Wolf.

David Wolf, the Fire Chief for the Estes Valley Fire Protection District. Wolf helped coordinate evacuations in the Estes Valley, as the East Troublesome Fire burned in Rocky Mountain National Park. Courtesy of David Wolf.

On Oct. 22, David Wolf, Fire Chief of the Estes Valley Fire Protection District, received news of the swiftly approaching East Troublesome Fire. The data, obtained from a signal on a satellite, revealed that the East Troublesome Fire had crossed the Continental Divide. But despite this data, there was still some uncertainty as to whether this had actually taken place.

“We had some further discussion about it, whether or not we could confirm that there was fire, and couldn’t get someone up there with the conditions. At 8 o’clock I got a call back. We still didn’t think it was over. So again, the Estes resources mobilized down in Glen Haven continued working on the Cameron Peak fire. About 11:30 that morning I got a call back on the radio from our emergency manager, letting us know that they had confirmed they had fire on our side of the Divide in the national park,” Wolf said.

Wolf immediately went to the Emergency Operations Center in Estes Park. He connected with his firefighting team there, as they prepared for evacuations in the Estes Valley. His main role was helping to direct these evacuations, beginning near the YMCA campus, and the Fall River areas of Estes Park. Wolf worked with the emergency manager, to order evacuations throughout the Estes Valley.

The time between the fire’s first crossing of the divide, up until it reached Estes Valley, was extremely rapid. Within a few days, the East Troublesome Fire was already making serious headway in Rocky Mountain National Park.

“By the time that we knew we had fire on the east side of the divide, the timeline was so compressed that we’re now essentially evacuating the entire Estes Valley all at once,” Wolf said.

Wolf and the other firefighters began to directly feel the impact of the evacuations. The fire had quickly become personal, as they watched friends and family leave Estes. The East Troublesome Fire was no longer out of reach, it was right on their doorstep, threatening the very safety of the firefighters’ families, friends and neighbors.

“Once we started evacuations, it wasn’t just this abstract concept. We knew people who were being evacuated. We had our own families being evacuated. My wife and two young kids, four and six years old, and the dogs are loaded up and driving out of town, while I’m staying to work on the fire,” Wolf said.

Meanwhile, firefighters from the Estes Valley Fire Protection District, in conjunction with law enforcement, assisted with the evacuation of Estes Park. They traveled door to door, notifying people about the encroaching fire, and the orders to evacuate.

“On the 22nd, as evacuations were happening, the sky was a dark orange in the middle of the afternoon, and winds were pretty sustained, 30 to 40 miles an hour throughout the day. But on the 22nd there wasn’t a whole lot of engagement with the East Troublesome Fire, because it hadn’t made it down to town yet,” Wolf said.

On the night of Oct. 23, the East Troublesome Fire started to move into the Estes Valley. The Estes Valley Fire Protection District immediately began working with the Incident Management Team to call in resources.

On Oct. 24, Wolf and other Estes Valley firefighters prepared local structures for the approaching fire. This involved protecting these structures, through the removal of flammable materials and other possible fuels.

The actual firefight began on the 24th, at around 2:00 in the morning. The Estes Valley was mostly deserted at this point, the sky dark, and the roads empty.

“Driving through a tourist town in the middle of summer with empty streets is a weird feeling. You’re standing outside getting blasted in the face with this 50-mile-an-hour dry wind, you can smell the smoke, but you can’t see the fire. You don’t know where it is. And so that was a little unnerving,” Wolf said.

Aftermath of the East Troublesome fire in Rocky Mountain National Park when entering from Grand Lake on March 6, 2021. Trail Ridge Rd remains closed about 9 miles in from the Grand Lake entrance. Photo by Katchene Kone.

Also unnerving are the numerous risks that the fire’s aftermath poses to the many communities across the state.

Because the East Troublesome Fire burned so late into the fall of 2020, wildfire recovery efforts have so far been minimal, but experts say extensive work awaits. And with snow now covering the majority of wildfire debris, it’s difficult to say what the damage underneath looks like. Despite this, Northern Water has started to take some preliminary steps toward fire recovery and cleanup.

Northern Water guides water resources for delivery to communities within eight different counties, stemming from Boulder County all the way out to the Nebraska state line. Not only do they deliver water to over a million people across northern Colorado, but also to more than 600,000 acres of irrigated agriculture.

That mission now faces some risks by the aftermath of the fires. In the hopes to mitigate the threats, which range from contaminated watersheds to fears of flooding, on Feb. 11, the Northern Water Board of Directors agreed to become a co-sponsor, along with Grand County, for the Emergency Watershed Protection Program (EWP). EWP is a federal emergency recovery program, administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture through the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

“What happens is that after a wildfire comes through, teams go out and evaluate what kind of damage has occurred and what are the threats to life and property in subsequent years,” said Jeff Stahla, public information officer at Northern Water.

After a wildfire of this size, it is important to look at what problems the damage left behind can cause. The number one thing on Northern Water’s radar is the possibility of flooding caused by a backup of debris. Northern Water’s goal, in tandem with EWP, is to predict possible scenarios for damage and see how much it will cost to address them.

“In late February we went out to Grand County with engineers and experts to look at people’s property and figure out what the risk is for debris clogging something up which would then cause flooding,” Stahla said. “We looked at a whole bunch of possibilities and scenarios for what damage could occur and now we’re in the process of figuring out how much it will cost to address all of those possibilities.”

The East Troublesome Fire has also had an impact on the Colorado Big-Thompson Project, which is run by Northern Water. About 80% of the water in Colorado lands on the west side of the Continental Divide, while 80% of the population and the majority of irrigated land is found east of the Divide. In order to get the water west of the Divide over to the east, the Colorado Big-Thompson Project collects water in the Colorado River Basin and delivers it to the Big Thompson Watershed for distribution.

Keeping the watersheds clear of wildfire debris is a key focus for Northern Water, because their primary goal is to make sure that the water they deliver to communities across Colorado stays clean. However, due to the magnitude of the fire, that debris has begun spread into key watersheds that deliver water to different counties across Colorado.

The frontline of the fire moved 15 to 17 miles in one day, crossing a small area of the watershed that we depend on for water, to then enveloping a much larger percentage of it. One of the watersheds that the fire devastated the most was the watershed for Willow Creek.

“Willow Creek is a tributary of the Colorado River and it is captured and stored in what is called the Willow Creek Reservoir, just northwest of the town of Granby,” said Stahla. “And as the fire really blew up that day, it careened across basically the entire Willow Creek Watershed, and then moved over a hill into the Colorado River Watershed.”

After moving through two main watersheds, the East Troublesome Fire then jumped the Continental Divide and ended up in the Big Thompson Watershed above Estes Park. Because of this, the main areas that Northern Water uses to capture and store water for future use is now in an area that has significant burn damage around it.

All of this burn damage consists of several things, including tree debris, plant material turned into ash or sediment and soils that are heavily burned which then become hydrophobic. All of these factors make flooding an inevitable possibility, as well as the plant debris getting deposited into creeks and lakes.

“As the tree debris falls down, it will create little dams and create places where water gathers that normally it hasn’t gathered before, and that’s going to create problems with flooding and damage to infrastructure,” Stahla said. “The soils that also got heavily burned become hydrophobic, causing the water to bounce off the ground rather than percolating into it, which will cause flooding.”

Ash and debris leftover from the East Troublesome Fire outside of Rocky Mountain National Park in Grand Lake on Nov. 7, 2020. The fire burned more than 100,000 acres on Oct. 21, 2020. Photo by Katchene Kone.

Todd Boldt, EWP Coordinator for NRCS, has been working in some capacity in EWP within NRCS since 1997, starting with EWP full-time in 2015.

“I can say this, when it comes to the East Troublesome Fire, I haven’t seen a situation like this in my 23 years of working on EWP. It is complicated, it is very complicated,” Boldt said.

No recovery after a fire is easy, they’re all complicated because each one is different. What makes this fire recovery especially complicated is that because it grew so large, it burned on many different types of land, including the Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain National Park, and private land. There are a lot of water assets spread throughout these burned lands, so NRCS has to figure out a way to bring all these factors together in order to move forward with recovery.

With every forest fire that hits Colorado, NRCS tries to learn something new, figuring out how to do things better for the next one. Since Boldt started full-time in 2015, he and his team have tried to incorporate the lessons learned going forward.

As we approach the 2021 fire season, EWP has a strategy to incorporate those new lessons and ideas into how they would approach the next forest fire. A lot of those ideas were based on lessons from 2018 with the Spring Creek Fire, the 416 Fire, and the Lake Christine Fire.

The main thing that EWP learned coming out of the 2018 fires was the process of data collection. This is a strategy that they incorporated into the 2020 fire season and are continuing into the 2021 fire season. The main focus being data analysis from a hydrology and hydraulics standpoint.

Hydrology refers to the water actually reaching and hitting a watershed, while hydraulics is how the water reacts once it gets into the watershed. EWP focuses on these two things so they can understand where potential impacts are going to be in certain watersheds. Based on data from 2018, they were able to tell how much water will be in a certain place or know which places won’t be impacted directly by a certain rainfall event.

The USDA Forest Service created a debris flow map which highlights the probability of that debris being in certain areas after the 2018 fires. Because EWP attempts to reduce erosion, sedimentation, and the threat of future flooding, they are able to look at that map to try and understand which areas could be affected the most.

EWP’s biggest focus is to reduce soil erosion, sedimentation, and flooding, the three main threats to life and property.

“Monsoon season is a big threat because if water gets dumped on one of those burned watersheds, you’re going to see an increase in flow rates of water coming off the hill which means increased flow rates going down the stream,” Boldt said. “And with no cover up there you’ll see increased soil erosion which moves off hill and eventually causes sedimentation issues and debris issues in rivers.”

As EWP rushes to bolster recovery efforts in advance of the coming fire season they have discussed a change in the way that they approach the critical phases of wildfire management – responding to the fire and recovering from it – more seamlessly.

“We need to start the recovery process when we are in the response phase,” Boldt said. “We need to integrate both of those processes so we can hit the ground running with great data early in the recovery process.”

Integrating these two processes will help local and state entities involved in the recovery phase. It would provide them with information to make decisions and help to make those decisions quicker and more informed on what the potential effects could be post-fire.

The EWP has played a crucial role in aiding large-scale recovery after the East Troublesome Fire. But recovery efforts have extended even further, reaching far beyond this federal program.

The charred remains of a bush, with a burned forest landscape in the background. Taken in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Another key entity, which has played a significant role in post-fire recovery, is the BAER team. These special groups, known as Burned Area Response Teams, operate under the U.S. Forest Service.

BAER teams are a wide ranging group of specialists, working together to bring about post-fire recovery and stabilization.

“The types of specialists that might be on a BAER team, in addition to a communications person, are a hydrologist, a recreation specialist, a wildlife person, a botanist, an archeologist. Depending on the area that it burns, you might have a different collection of experts,” said Reid Armstrong, the Public Affairs Specialist for a BAER team.

BAER teams work in Forest Service lands throughout the United States. Their primary goal is to stabilize areas that have been heavily impacted by fires.

Their rehabilitation efforts occur over lengthy time frames, often beginning as fires burn across Forest Service lands. But usually BAER teams start their recovery work after forest fires have been mostly contained.

“When the fire is burning, a large fire like this, we bring in incident management teams. So our forest employees aren’t necessarily out there fighting the fire after the initial attack. We’re bringing in a team of experts,” Armstrong said.

Stabilization efforts continue for as long as is needed, sometimes up to a year after a fire has ravaged through a wilderness area. Long term rehabilitation continues for several years after a forest fire.

Reid Armstrong’s BAER team, based in the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forest, has taken part in the East Troublesome Fire recovery efforts.

For Armstrong’s BAER team, East Troublesome rehabilitation was quite different from previous recovery efforts. This was mainly due to a significant snowfall, which played a key role in slowing the fire. But in spite of the positive impact of this snowfall, the snow made it difficult for her team to carry out their responsibilities.

“Snow fell right after the fire was burning, and so that created this huge challenge for us, in actually getting in there to see some of what happened, or to do any of the emergency efforts,” Armstrong said.

The East Troublesome Fire was unlike anything Armstrong had seen before. Its rapid growth differentiated it from other fires she had dealt with in the past.

“From a BAER team perspective, I think that when a fire moves that fast, often it doesn’t actually have time to smolder, and do as much damage. It was wind driven, and it blew through the treetops, but it didn’t have time to creep and crawl, and burn all the kind of real stuff down below,” Armstrong said.

The fire’s rapid growth prevented it from further damaging the natural environment. But despite this, the overall human impact of the East Troublesome Fire was immense. This is something Armstrong noticed, after her team further evaluated the post-fire effects.

“From an ecological standpoint on the forest, there isn’t that much, from what we can tell, high burn severity soil. There are some small pockets with high burn severity, but when you look at the vast however many thousand acres, it’s mostly low burn severity,” Armstrong said.

The East Troublesome Fire moved quickly, and as a result, didn’t have time to significantly damage the soil. According to Armstrong, this is what differentiated this fire from other early season fires. These other fires burned longer and slower, leading to a larger impact on ecology and the environment.

Armstrong’s team also examined the fire’s effects on streams and rivers. One of their primary concerns has been the post-fire contamination of drinking water.

Streams and rivers in Forest Service lands run into reservoirs. Armstrong’s team is worried that if snowmelt occurs in high burn severity areas, contaminated water will run into these streams, eventually ending up in the reservoirs.

This would have quite a significant impact, considering the fact that reservoirs provide drinking water for many people. In addition, silt left in the wake of the fire can also increase the likelihood of flooding.

“That kind of silt and debris can create floods. It can really mess up the infrastructures, the intake systems, the filtration systems, all of that,” Armstrong said.

According to Armstrong, in order to remedy these aftereffects, her BAER team would need to focus on slowing the water’s movement. They would also need to prevent debris from piling up against varying aspects of infrastructure.

But ultimately, Armstrong’s BAER team is still in the process of assessing fire damage, as well as carrying out rehabilitation efforts.

“The team will have to go back and do some further assessments, after the snow melts. And secondly, some of the methods they did identify, responses they wanted to do, they weren’t able to do because of the snow,” Armstrong said.

Entering Grand Lake, CO via Highway 34 on Apr. 24, 2021. Some of the damage caused by the East Troublesome Fire can be seen on the mountainside behind. Photo by Katchene Kone.

Keith Kraatz, owner of Studio 8369, an art gallery in Grand Lake, lost his home to the East Troublesome Fire in Oct. 2020.

Kraatz and his wife moved to Grand Lake eight years ago from Kansas City. They always dreamed of being in Grand Lake and when the opportunity presented itself to move, they took it, purchasing a little fishing cabin built in the 1950s and remodeling it into something of their own.

“It was a very cute little cabin, and we poured our hearts, souls, sweat, blood, you name it into making that what it was,” Kraatz said.

On Oct. 21, the day the East Troublesome Fire burned through the town, Kraatz and his wife had artwork to deliver down in Denver. They left that morning, not knowing that the fire would soon be spreading through their community. Kraatz noted that when they reached Denver he made a comment that Cameron Peak Fire must have really taken off. But little did he know, he was watching East Troublesome.

Because reports on Facebook indicated that they would probably have a few days' notice before needing to evacuate, Kraatz didn’t bring a go-bag or anything else with them on their day trip to Denver.

Once they got the alerts that Grand Lake was being evacuated, they tried to get back up, calling people they knew in the Grand County area, only to be told that the traffic was all one-way, both lanes from Grand Lake to Granby.

“We just turned around and listened to the scanners the rest of the night,” Kraatz said. “I know the fire marshall up here, so the next day I called Dan and I asked him to just go by our place and he did and he just said sorry but you guys didn’t make it.”

When Kraatz moved to Grand Lake, they downsized from a home about 4,200 sq/ft to 1,200 sq/ft. In doing so, the only things they brought with them were the sentimental items.

“You go from the morning going down, let’s take a trip to Denver, eat at a different restaurant, deliver art -- to we lost everything and now we have our clothes on our back and the vehicle we’re driving, and that’s it,” Kraatz said. “Now we’re living out of suitcases and storage bins because there was absolutely nothing left”

Coming to terms with what happened has been hard for Kraatz. Everything he and his wife had worked for suddenly disappeared, leaving them in a position where they have to completely start over.

“You have your good days, I mean there’s days you know what you’re dealing with,” Kraatz said. “But then there’s days that it just hits you right square in the face and you just ask yourself, what are we gonna do?”

As the warm weather has started to move its way into Grand Lake, there has been an increase in snow melt, uncovering the aftermath that the fire left in its path. With snow starting to melt, Kraatz has found difficulty in trying to move on from what happened, being faced with the gravity of the situation all over again.

“Now we’re dealing with all this snow melt and we’re seeing all this black and ash come back and you’re like ‘oh my god’ just look at this,” Kraatz said. “Your wound was starting to close just a little bit and now we’re just gonna cut it wide open again.”

Kraatz and his wife are now faced with the difficult decision of whether to stay in Grand Lake and restart completely, or move away. Their daughters live in Washington state and are pushing for them to head that way and be closer to them and their grandkids, leaving a lot of decisions to be made.

Fortunately, Kraatz's art studio, along with the rest of the town of Grand Lake, was saved by the firefighters. Kraatz was incredibly thankful that the town was able to be saved from the fire, noting that if the town had not been saved, it would have been very difficult for the town of Grand Lake to come back due to the fact that it is heavily tourist driven.

“Thankfully, the support of the town has helped the businesses keep our heads above water as we go forward,” Kraatz said.

Grand Lake resident Keith Kraatz's home in Sept. 2020, a month before the East Troublesome Fire came through the town. Kraatz and his wife moved to Grand Lake in 2013 from Kansas City. Courtesy of Keith Kraatz.

Grand Lake resident Keith Kraatz's home after the East Troublesome Fire destroyed it on Oct. 22, 2020. The Grand Lake Fire Marshall sent the Kraatz's a photo of their empty lot before they were allowed back into the area. Courtesy of Dan Mayer.

Tucker Merz, a homeowner in Grand County, and owner of a tree removal business, was working when he first heard about the fire. While driving back to Granby from Grand Lake, Tucker saw large plumes of smoke. He quickly drove back to his home, located on Highway 125 outside of Granby.

From that point onward, Tucker continued going to work every day. Each night he packed up a few of his belongings at a time, to prepare for the possibility of a sudden evacuation.

“When the smoke and haze and orange glare started getting stronger and stronger, I became a little bit more worried. I started packing up valuables and things that my family had left, and you know, just everything that meant a lot to me,” Merz said.

Over the next few days, the East Troublesome Fire grew rapidly in size. Extremely high winds fueled the fire, causing it to quickly gain momentum.

At 11:00 on Friday night, Merz received a call, letting him know that evacuations would occur in the morning. All night long Merz hauled trailers into town, packed with both his and his roommate's belongings.

“By Saturday morning we had gotten quite a bit of stuff out. Not everything obviously, but my roommate and I both had a couple trailers worth of stuff to get out,” Merz said.

Soon thereafter, Grand Lake was evacuated. Merz still had some belongings in Grand Lake, where he was temporarily staying at the time.

“I ran a road block from the police, and drove all the way to Grand Lake, and got my own stuff. I helped out everybody I could on the way out,” Merz said.

Merz ended up losing his home to the East Troublesome Fire. The fact that the fire was able to reach his home surprised him.

“I wasn’t really concerned about my place, because I don’t have a whole lot of trees around it. I honestly don’t have any trees within 600 yards, besides maybe 30 or so landscaping trees. And I never thought it would come through,” Merz said.

But moving forward, he hopes that fire mitigation will be significantly pursued in Colorado. Otherwise, Merz believes that fires of the same magnitude could occur in the near future.

Keith and Laura Kraatz's art studio in Grand Lake, CO on Apr. 23, 2021. The studio did not sustain any fire damage, however some can be seen on the mountainside behind the town. Photo by Katchene Kone.

Before losing their homes to East Troublesome, Olson and the Kerns had done considerable work to protect them against wildfires.

Over several years, Olson had cleared vegetation from underneath her decks, cleared the gutters and roof of pine needles, surrounded the entire house’s foundation with 5 feet of rocks, spaced out and removed limbs of surrounding trees, stacked firewood at least 30 feet away from the house and removed dead and dying lodgepole. She had a roof with a Class A fire rating, which is the most resistant to fire. She had dual-paned windows with tempered glass, which resists breakage. The outside of her home was built with non-combustible materials, and the building was made out of heavy timber to avoid collapse. Jodie and Donnie Kern had no trees within 30 feet of their house, fire-resistant cement siding and asphalt shingles, which are not flammable.

It wasn’t enough.

“The East Troublesome Fire blow-up on Oct. 21 was a tremendous firestorm,” Olson said. “The winds, topography and dead lodgepole pine forest aligned to create such extreme fire behavior that no amount of mitigation would have changed the outcome in many areas.”

“We thought that we did everything right,” Jodie Kern said. “But there was going to be no saving the house at all.”

But Olson emphasized that the smallest mitigation actions “can make the difference in ‘normal’ wildfire situations.”

“The fact that this fire was just so extreme, and there probably wasn't anything more than I could have done at my house… (but) the message can't be just, ‘give up,’” Olson said. “If it's gonna happen, it's gonna happen. We still need to do those little things that help with mitigation and help homes survive.”

A charred area in Rocky Mountain National Park on April 3, accompanied by a sign which reads "NO FIRES." Photo by Anna Haynes.

A burned tree stump surrounded by fallen and burned branches in Rocky Mountain National Park on April 3. Photo by Anna Haynes.